Are you looking for new ways to engage your students in Latin or the ancient world? Taking a trip to an ancient schoolroom might be just the thing! In this post, Professor Eleanor Dickey explains how the Reading Ancient Schoolroom came about, discusses the activities on offer and the historical evidence upon which they are based.

Submitted by Anonymous on Tue, 17/10/2023 - 16:11

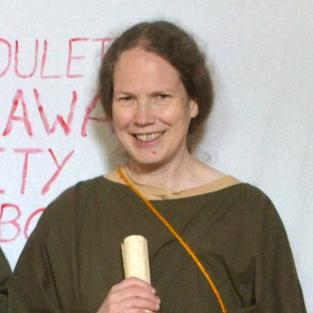

Pupils prepare to recite in the ancient schoolroom

Can ancient teaching methods work today? Most of us tend to assume that the answer is no, both because the educational changes since antiquity are by definition progress and because modern pupils are so different from ancient ones in background, outlook, and expectations. Yet when University of Reading colleagues and I tried to re-enact lessons from the ancient Latin textbook known as the Colloquia of the Hermeneumata Pseudodositheana, the results were surprisingly good.

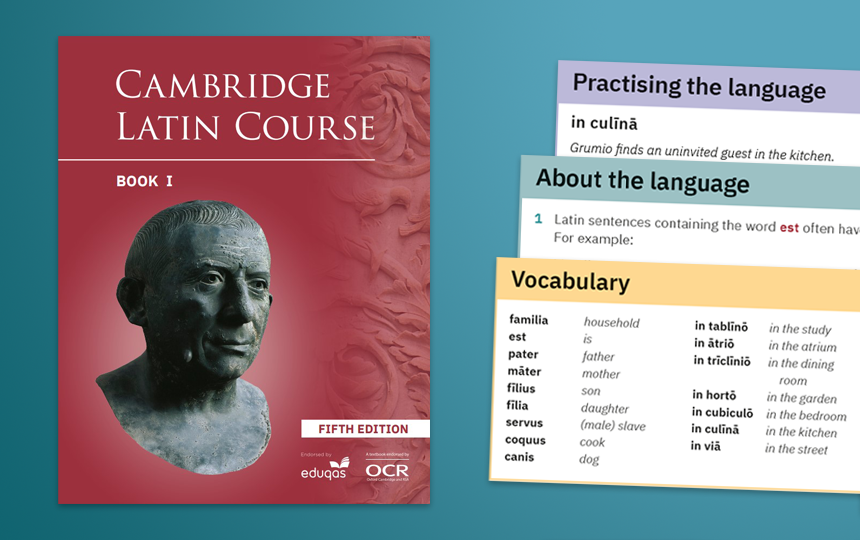

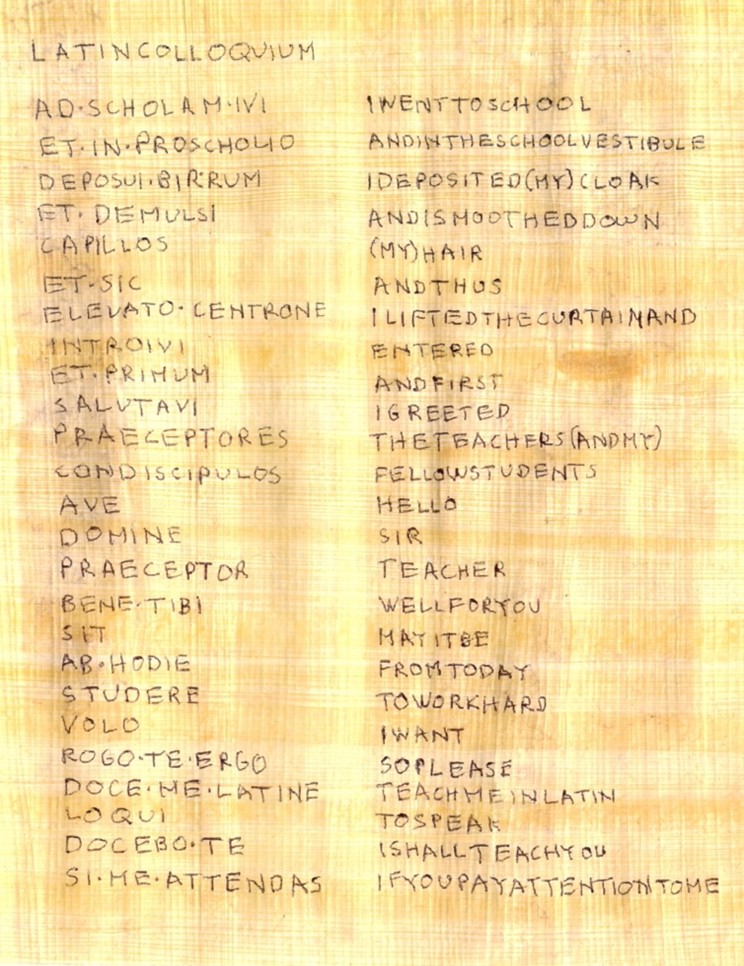

This experiment was part of the Reading Ancient Schoolroom, a project to give modern children the chance to immerse themselves in a historically accurate reconstruction of an ancient school. Originally our ancient school taught only reading from papyrus rolls, writing on wax tablets and ostraca, and ancient mathematics, but soon teachers were asking for ancient Latin lessons as well.

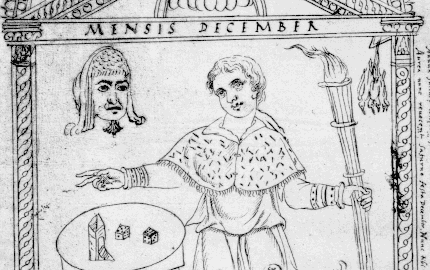

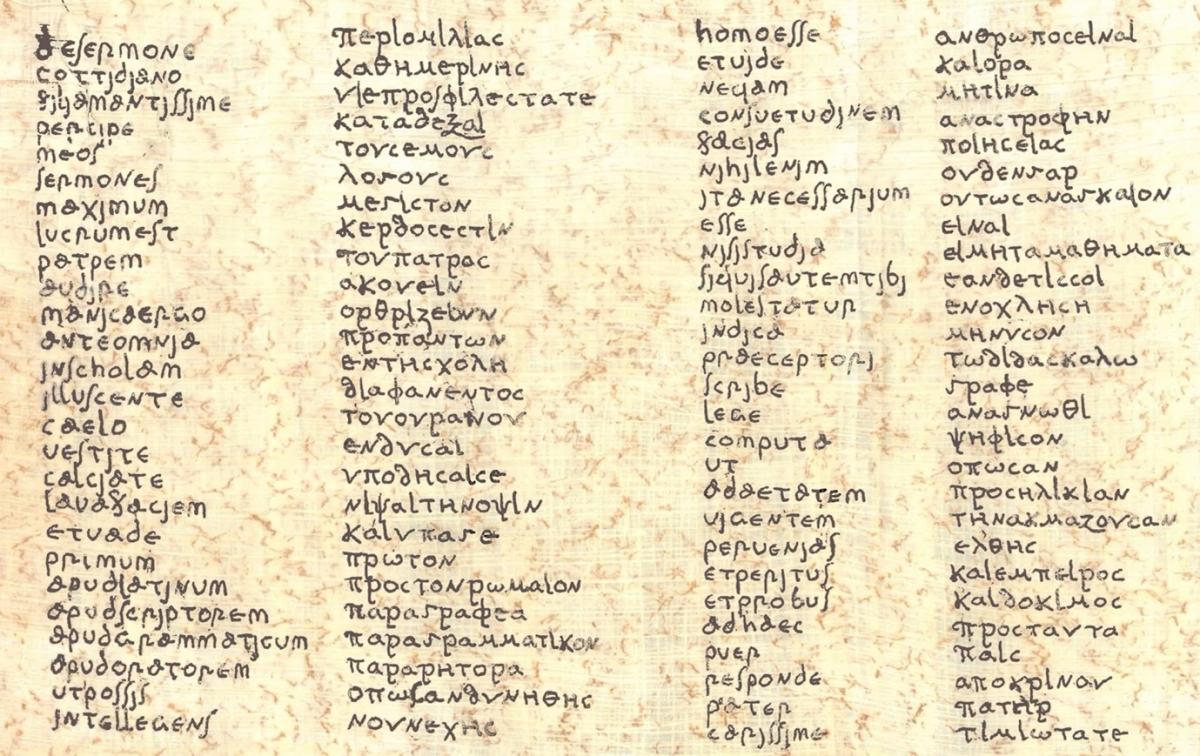

Ancient Latin learners started their studies with dialogues about everyday interactions, such as bathing, borrowing money, dining, going to a temple, or making excuses. The dialogues are short, lively, idiomatic and written in clear and straightforward Latin – and like the dialogues found in foreign-language textbooks today, they aim to reveal Roman culture as well as language. The original target audience consisted of Greek speakers, who were not bothered by declensions or conjugations, and therefore a full range of forms appears from the very beginning. But the difficulties posed by these forms is moderated by provision of a running translation.

When I first realised that ancient Latin teachers gave their pupils this translation, I was confused. Why would anyone do that? Because, it turns out, the dialogues were originally presented without word division, meaning that pupils could not work out where the Latin words began and ended (and thus could not use a glossary) until they had learned a lot of vocabulary. So their initial Latin lessons were mainly aimed at building vocabulary while keeping pupils engaged enough to survive the vocabulary-building period and reach the point where they could start to tackle Latin independently.

But what can you do in class with a bilingual dialogue? You cannot ask pupils to translate it, since there is already a translation. Instead, pupils use the translation to work out what the Latin says (not only what the words and grammar mean, but also where the punctuation goes, which lines are spoken by which characters, who the characters are, etc.). Then they learn the Latin and perform it to a teacher. This is ideally done in pairs, so that one pupil can play each part. And that collaboration prevents the pupils from getting stuck and giving up; they help each other out and end up with something better than either could have produced independently. Moreover, in the performance itself there is very little stage fright, since no-one except the teacher is watching.

How authentic can one make the presentation of the dialogue? We sometimes use exact replicas of the original papyri, but only for the most advanced students; most pupils need the translation to be in English rather than Greek, for the letters of the alphabet to have their recognisable modern forms, and for the Latin to have word divisions. The English, however, does not need word divisions, since in the ancient schoolroom we normally start with an exercise in reading English without word division and move on to Latin only after pupils have learned that skill. And neither part needs punctuation or speaker designations; the dialogues are designed so that pupils can work those elements out for themselves, as ancient readers normally did. So our Latin exercises are sometimes presented in a format very close to the original.

At an intermediate stage ancient pupils were slowly weaned off bilingual texts by being given running glossaries containing only the words or phrases they did not yet know, until they had enough vocabulary to divide the words themselves and use a dictionary. This intermediate level can also be replicated in the ancient schoolroom; usually we offer the pupils’ regular Latin teacher the chance to decide which words will be glossed, to make sure that our exercise is precisely suited to their knowledge. Both we and the regular teacher can also circulate as the students prepare to perform, helping any who need an extra hint. Advanced Latin exercises, with few or no glosses, can be done in the same way. Ancient students began learning languages at a wide variety of ages, from the Romans who learned Greek in or even before primary school to the Greek speakers who learned Latin when they got to law school. Therefore exercises suitable for all ages exist; the ancient schoolroom most often does Latin classes for pupils in years 5, 7, and 9, but we can offer something to suit pupils at any stage. Mixed-age and mixed-level groups are also fine, since each pair of pupils works independently of the others.

The Reading Ancient Schoolroom has recently registered as a charity and has received an AHRC grant to help it expand and bring the joys of ancient learning to more pupils by travelling to interested schools. Although we usually need to charge to cover the costs of putting on an event, the grant includes some money for free and subsidised events at schools that cannot afford to pay the full cost. That money is only available until 15th May 2024, so we would particularly love to hear from schools who would like to give their pupils ancient Latin lessons before that date.

First and second image: Claire Smith; Remaining images: Eleanor Dickey