Working towards inclusivity in the Classics classroom is a combination of what we choose to teach and how we choose to teach it. In this post, Rob Hancock-Jones shares some of his experiences teaching Classical Civilisation making use of diverse and inclusive visual aids.

Submitted by Anonymous on Wed, 05/05/2021 - 17:38

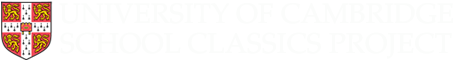

A montage of three of the 'Fayum' mummy portraits discovered in Egypt and dating from the Imperial Roman era.

Every September my classroom welcomes a new cohort of GCSE Classical Civilisation students. Some are eager to make a start on this new stage in their education, others seem trepidatious about what to expect from this “new subject” (I do enjoy the irony that the most ancient subject on our school’s curriculum isn’t offered in Key Stage 3, so to the GCSE students it’s all “new”). I put the students in their seating plan, settle them down, take the register and then I begin the process of unlearning.

Yes, unlearning.

Although none of my Year 10 students have formally studied Classical Civilisation before, they come armed with a whole host of preconceived ideas about the ancient world. They begin the course not as a tabula rasa (blank slate), but more like past-their-prime whiteboards, bearing marks left by everything ancient or pseudo-classical they’ve ever come into contact with. From the pages of Percy Jackson and clips from Horrible Histories, to half-remembered anecdotes from Primary School and much-loved myth books from childhood. These learners come pre-loaded with a hodgepodge of information about the ancient Mediterranean.

In some ways, I love this. I take great pleasure in breaking the news that after the end of the Disney movie Hercules goes mad and kills the children that Meg had with him. The shock on their faces morphing into disgust that they’ve been so badly misled by The Walt Disney Company is a watershed moment in their understanding that not all sources are reliable. The emotional rollercoaster of shock and disgust ensures that the lesson is learned – do not trust something just because it’s got a great soundtrack.

This example, of disabusing students of their rose-tinted Hercules, is fairly light-hearted, and I would never criticise a colleague who decided not to correct this story when a student (inevitably) brings it up. But there are other, more insidious messages that our students bring into the Classical Civilisation classroom. And it is these messages that we, as educators, need to take the lead in dismantling.

***

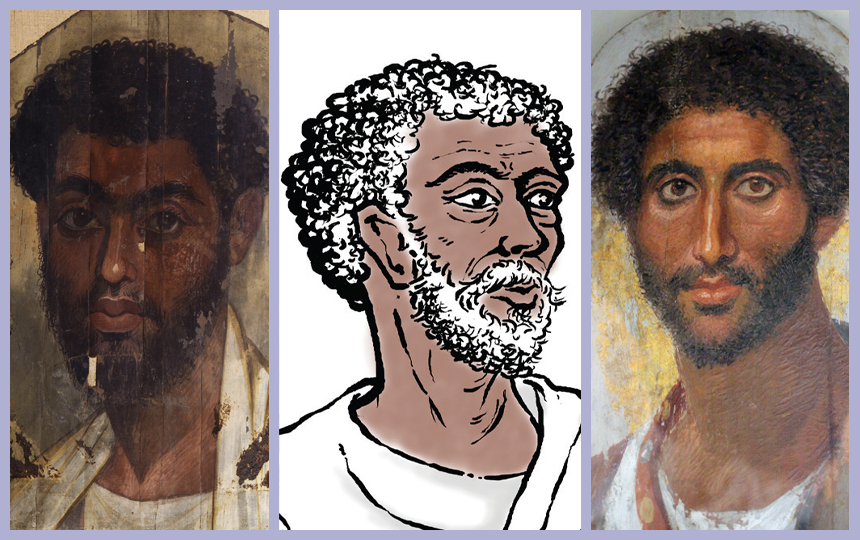

The vast majority of media that my students are exposed to before entering my classroom depicts the denizens of the ancient Mediterranean as white, Northern/Western Europeans. Popular recent film and TV adaptations of ancient stories, such as Troy (2004), the Percy Jackson films (2010, 2013) Horrible Histories (2009-present) cast white actors in the majority of roles. Older films that have achieved the status of “Classics” in their own right, such as Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra (1963), not only cast white actors in the majority of roles, but makes use of Black actors in exclusively servile roles (see for example the famous “Cleopatra Enters Rome” scene in which Cleopatra’s throne is depicted above (quite literally carried on the shoulders of) Black bodies. And this phenomenon is not limited to the screen. A review of my local libraries’ collections of books aimed at KS1-3 learners revealed a similar picture. Whether the images were depicting the gods, artists, actors, politicians, soldiers, farmers or families, the cartoons, mannequins and photographed reconstructions almost all featured exclusively white people.

And so, not unreasonably, the average Year 10 GCSE Classical Civilisation student begins their journey with the misapprehension that the ancient Mediterranean was peopled almost exclusively by white people. This is hugely problematic, for a number of reasons. It can put students off the discipline, as they may perceive it is not reflective of them or does not “belong” to them. Moreover this misapprehension, combined with the rarefied position of the Greeks and Romans in terms of their cultural capital and perceived exceptionalism, also gives rise to white supremacist ideas, as Rebecca Futo Kennedy has amply demonstrated.

***

One of the simplest ways of combatting our students’ misunderstandings of the ancient world’s diversity is to consciously and continually make use of diverse visual aids in our teaching.

When looking to illustrate myths on a lesson PowerPoint, it’s tempting to make use of whatever is freely available on Google Images. Take, for example, Dido the queen of Carthage. She is a great example of African excellence (that is before her cruel mistreatment by the gods and Aeneas in Virgil’s account) and all A Level Classical Civilisation students encounter her in the Aeneid. But a Google Image search returns a collection of Renaissance paintings of pale bodies. If we “cast” Dido with any of these images, are we not engaging in a similar process to the whitewashing that Hollywood has come under fire for in recent years? But Google Images isn’t useless! You simply need to scroll down a bit. If we look beyond the first few results, where the algorithm seems to give precedence to these oil paintings, we see images of Black women portraying Dido on the stage. Why not use these instead of the Renaissance images?

While I’m on the topic of Google Images and the importance of scrolling down the page a bit, do a search for something like “thinking”, “philosopher”, “politics” or “professional”. The first few images that these return are overwhelmingly white and male. As classroom teachers, Google Images is surely our first port of call when sourcing images to spice up presentations. It pays to be aware of the biases that exist within this tool, and to take conscious steps to ensure that they don’t spill-over into our lesson resources.

OK, aside over, back to antiquity.

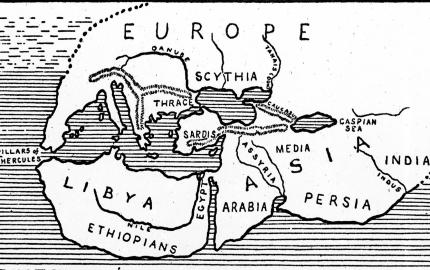

Another great source of diverse visual aids that comes from antiquity itself is Egyptian mummy portraits, like the ones at the beginning of this post. As these were painted in a naturalistic style, they provide a more reliable impression of the appearance of their subjects than other, more stylised art forms from the ancient world.

Speaking of stylised art forms, using black figure or red figure vase paintings can be another way to improve the diversity of representation in your lesson resources. Stylised though they might be, the men and some of the women depicted in these images have black or red/brown skin tone. Again, this serves to destabilise the impression created by more contemporary media of the whiteness of the ancient world.

Even pottery which depicts pale skin can be used to make our classrooms more diverse and inclusive. Take for example this scene, which depicts women working in the gynaikon. They are presented indoors, and their skin is bright white. Inform your students that women were often painted with this white pigment but men never were (rather they would be rendered in black or brown), and ask what they think the reason could be. They may relate this to their study of History (they all do the Tudors at some point and in that topic see the ghostly white depictions of nobles like Elizabeth I) and suggest that it’s conveying the status of the women, who don’t go outside and therefore are untanned. This is another great learning moment, because it introduces students to the idea of a visual language, where art is not photographic, but rather symbolic.

***

Finally, a word about white marble statues. As argued by Sarah Bond, “the equation of white marble with beauty is not an inherent truth of the universe; it is a dangerous construct that continues to influence white supremacist ideas today”. The answer is not to keep images of white marble sculpture out of our classrooms, but to take the time to provide context to our students about these white marble sculptures to help them understand that they do not, in fact, provide evidence of prevailing whiteness in the ancient world.

Teach polychromy, the idea that ancient marble sculptures were brightly painted, and show examples of sculptures where original pigment is still visible (Bond’s article is a great starting point for this, but there are plenty of examples to be found online, especially from subterranean tombs). You could spend time discussing how archaeological practices have evolved over time in response to the recognition of the historical truth of polychromy, so we no longer take newly unearthed sculptures “round the back” to be hosed-off (a practice which removed not only loose earth, but also the original pigment).

Another fun and useful activity is to invite speculation of what the original paints might have looked like. Take this Athenian grave stele for example. The seated figure is holding her hand up, in a way that suggests she is holding something. Surely something was painted on – engage students in a debate over what it could have been. If you have time, your students could do some colouring-in to bring the image back into technicolour, and show their understanding of the topic by making sensible additions to the background (a loom perhaps?).

***

I do believe that visual aids are incredibly impactful. We project them onto a screen in our classroom, sometimes as the item up for discussion, sometimes just for decoration. And every time we do, our students spend minutes of their lives staring at them. Getting lost in the smallest details of these pictures every time we fail to hold their attention.

As such they present a problem and an opportunity. A problem if we unwittingly reinforce a message that our students come pre-loaded with: that the Classical World was all white guys from Oxford and pale Renaissance ladies. An opportunity if we consciously and continually use them to demonstrate the diversity of the ancient world in all its beautiful polychromy.

left: Pushin Museum, photo by NearEMPTiness, CC BY-SA 4.0; centre: Staatliche Museen, photo by Brück & Sohn Kunstverlag Meißen (cropped), CC BY-SA 3.0; right: Louvre, photo by Saliko (cropped), CC BY 3.0