How do we teach Greek and Roman culture in a rigorous and systematic way that honors the complexity and diversity of the peoples that inhabited the Ancient Mediterranean? In this piece, Evan Dutmer provides teachers with a simple framing tool that will help them to teach culture on both its surface and deeper levels.

Submitted by Anonymous on Mon, 15/11/2021 - 10:00

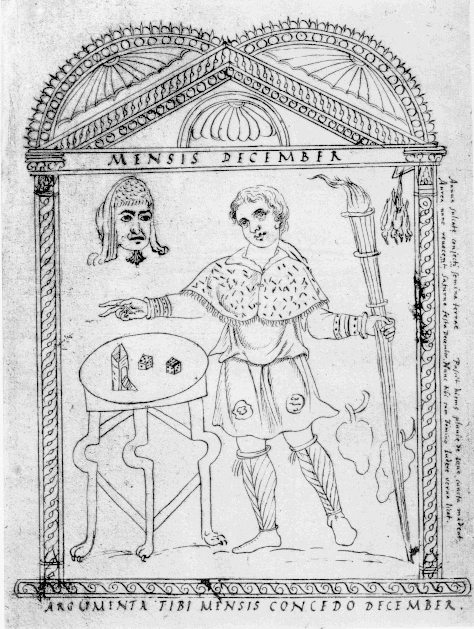

A drawing from Philocalus' calendar of 354 CE depicting a personification of the month of December, with Saturnalian dice on the table and a mask hanging on the wall above.

This piece appeared in a longer form at the Journal of the History of Ideas Blog.

One of the special gifts of teaching language is the opportunity to introduce our students to culture(s). But it can be difficult to know how to teach culture in a rigorous and systematic way. In fact, to enhance their students’ intercultural understanding, language educators should be careful to teach both what is generally called “surface” culture (e.g., types of clothing, food, fairytales, music, art—essentially the ‘facts’ of a culture) and the “deep” culture of a studied group (e.g., perspectives, values, history, narratives, ideas, and background beliefs that, in a sense, underlie the surface culture). In this piece I’ll give educators a simple tool for demystifying this process and ensuring that they teach culture on both its surface and deeper levels.

For Latin educators face this problem: excited to introduce Roman cultural practice into their classrooms, we may focus on the what and how of Roman culture rather than the why and who. Recreated celebrations of ancient Roman holidays in today’s classrooms can lack “deep” culture if conducted only on the surface-level. Students may wonder: Why did the Romans conduct their holiday ceremonies in the way they did? Who participated? Who didn’t?

Incorporating contemporary social history into Classics can help students and teachers access deep culture in the context of Ancient Mediterranean peoples. By thinking about and reflecting on how class, gender, race, ethnicity, and, broadly, identity functioned in the daily lives of the peoples of the classical world, students are able to i) gain a much richer understanding of their own culture—or, more precisely, cultures—and ii) better and more accurately examine Ancient Mediterranean cultural practice and knowledge.

The 3P Model, a pedagogical framework to deepen engagement with a cultural product in classroom teaching, is a powerful tool for developing this sort of deep cultural analysis in the secondary classroom and for adapting existing language acquisition activities into opportunities for intercultural learning. It asks that we make explicit the cultural product, practice, and perspective (the 3P’s).

I recently applied this framework to teach the Roman holiday of Saturnalia. Saturnalia celebrations are a common December tradition in many secondary Latin classrooms and in youth classical organizations around the world. In ancient Rome, Saturnalia was regarded as the finest and happiest holiday (optimo dierum, “the best of days”, in Catullus 14.15). Festive recreations often revolve around learning about the Roman god Saturn, decorating the Latin classroom leading up to a winter break, blurting out the customary Saturnalia greeting—“Io! Saturnalia!”—and gift-giving and dressing-up. Some instructors incorporate more of ancient Roman cultural practice; others focus on its possible ties to modern Christian rituals in the lead-up to the Christmas holiday.

Comparatively less focus, however, is paid to Saturnalia’s complicated relationship to the institution of Greco-Roman chattel slavery. The December holiday was associated with a sort of topsy-turvy “role reversal” of enslavers and enslaved persons, with a number of accounts detailing a banquet provided to enslaved persons by their enslavers. Enslaved persons may have also been invited to games, gambling, and poetry competitions, activities from which they were generally forbidden. This seasonal qualified freedom is encapsulated in Horace’s memorable description of Saturnalia as the libertas Decembri, “December freedom,” in Satires 2.7.4. Importantly, this season of ‘good tidings’ was explicitly and brutally temporary; the return to the rigid hierarchy of enslaver-enslaved returned every year by the end of Saturnalia, as memorably described by the formerly enslaved Epictetus in Discourses 4.1.58.

Horace’s Satires 2.7 contains a powerful speech delivered by Davus, a supposed enslaved person of Horace, who uses the license granted to him on the holiday to challenge Horace’s dominion and supposed freedom. He outlines ways in which Horace is in fact servile to his aesthetic tastes and desire for money and riches:

tu, mihi qui imperitas, aliis servis miser atque

duceris ut nervis alienis mobile lignum.

quisnam igitur liber? sapiens sibi qui imperiosus,

quem neque pauperies neque mors neque vincula terrent,

responsare cupidinibus, contemnere honores

fortis, et in se ipso totus…

You who command me are a subject to other things, and are led around like a puppet movable by others’ strings. Who then is free? The wise man who is in command of himself, whom neither poverty nor death nor chains frighten; courageous in checking his desires and in looking down on honors, and perfect in himself…

(Horace, Satires 2.7.80-85, my translation)

Using the 3P model, I’ve crafted a lesson plan around both the Satires text and a piece of secondary academic literature, in this case, Fanny Dolansky’s “Celebrating the Saturnalia: Religious Ritual and Roman Domestic Life” in A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Dolansky’s piece contains an excellent, thorough, and accessible introduction to the domestic and family dynamics of the Saturnalia festival.

In this lesson plan (found here), I chart the product, practice, and perspectives of Saturnalia through Horace’s Satires 2.7. The learning objectives of this lesson plan are that my students be able to identify the implicit values expressed by Roman celebration of Saturnalia, and gain a better appreciation for why they ought not to celebrate Saturnalia through the donning of traditional Roman enslaver-enslaved-freedmen garments or re-enact “slaves’ banquets” and “status inversions.” The ‘product’ in this case is Satires 2.7; the ‘practice’ is the ‘free speech’ or ‘December liberty’ (libertas Decembri) wherein enslaved persons acted out masters’ roles in planned banquets and ceremonies; the ‘perspectives’ are views surrounding the practice as enumerated in enslavers’ and enslaved persons’ opinions found in Satires 2.7 and Epictetus’s Discourses. I build on this model with potential classroom activities, language support, and scaffolding and connect the lesson with broader conversations surrounding the function of holidays within a slave-owning society.

For example, an important extension of this lesson includes discussion of the similar function of the Christmas holidays in antebellum US South as a form of “social conduction.” In the referenced lesson, I compare Davus’s speech in Horace’s Satires 2.7 with Frederick Douglass’s powerful reflections on the intended social control effected on enslaved people through the celebration of Christmas of New Year’s at the end of the calendar year. He writes:

From what I know of the effect of these holidays [Christmas and New Year’s] upon the slave, I believe them to be among the most effective means in the hands of the slaveholder in keeping down the spirit of insurrection. Were the slaveholders at once to abandon this practice, I have not the slightest doubt it would lead to an immediate insurrection among the slaves. These holidays serve as conductors, or safety-valves, to carry off the rebellious spirit of enslaved humanity. But for these, the slave would be forced up to the wildest desperation; and woe betide the slaveholder, the day he ventures to remove or hinder the operation of those conductors! I warn him that, in such an event, a spirit will go forth in their midst, more to be dreaded than the most appalling earthquake. The holidays are part and parcel of the gross fraud, wrong, and inhumanity of slavery. They are professedly a custom established by the benevolence of the slaveholders; but I undertake to say, it is the result of selfishness, and one of the grossest frauds committed upon the down-trodden slave. They do not give the slaves this time because they would not like to have their work during its continuance, but because they know it would be unsafe to deprive them of it…

Douglass 114-116

Douglass’s reflections make for a powerful tool of comparison in my classroom. The text helps students consider what first-person reflections of enslaved persons would have been during the “December liberty” and question who the festival was really for. It also provides us an opportunity to have rich conversations about the similarities and differences between the chattel slavery practiced by Ancient Mediterranean peoples and by modern European peoples. As one obvious point of contrast, we discuss the Transatlantic slave trade’s basis in race, absent in antiquity, while acknowledging the brutal features of the ancient system.

Consequently, at the end of the Saturnalia sequence in my courses (in this case, Latin 2), students are well-prepared to demonstrate intermediate intercultural proficiency in their spoken and written reflections on the Roman holiday. In fact, if we take a look at the official wording of the NCSSFL-ACTFL Can-Do statements for the intermediate proficiency, we’ll see that students who have been exposed to the 3P framework are well on their way to demonstrating intermediate intercultural proficiency:

INVESTIGATE In my own and other cultures I can identify and compare the values expressed by the ways people celebrate holidays or festivals.

INTERACT I can adjust the way I dress to make it appropriate for a celebration or event.

In the case of Saturnalia, my students are able to identify and compare the values expressed by Roman celebration of Saturnalia (and Christmas in the antebellum South, besides), and, in fact, have gained a better appreciation for why they ought not to celebrate Saturnalia through the donning of traditional Roman master-enslaved-freedmen garments or re-enact “slaves’ banquets” and “status inversions.”

The application of the 3P Model, I’ve shown, can be an important step in making Classics classrooms more culturally-literate, ‑nuanced, and ‑responsive. Careful attention to each element of culture as outlined in the model can significantly improve a Latinist’s engagement with both Ancient Mediterranean peoples and the diverse cultures of the human beings in the classroom.

Public Domain