In response to those who may think otherwise, Elena Giusti argues that the application of Race Theory and Critical Race Theory to the ancient world is far from a needless intellectual exercise. It enables teachers and students to connect antiquity and modernity while investigating our own biases and making us better interpreters of both societies, and of our own academic and pedagogical practices.

Submitted by Anonymous on Mon, 19/10/2020 - 17:18

Gypsum heads of Apollo and Aphrodite, unpainted.

Classicists often steer clear of the concept of ‘Race’. As Denise McCoskey points out in a recent interview, many in the field tend to speak of ‘ethnicity’ on the grounds that race ‘is not relevant in Classics’. But doesn’t this discomfort with discussing race tell us more about contemporary interpreters of the ancient world than the ancient world itself?

Objections to the use of Race Theory and Critical Race Theory when studying the ancient Mediterranean world are based on the premise that premodern societies predated the invention of scientific racism. It is thus claimed to be anachronistic and a-historical to apply Race Theories to the ancient world.

Classicists like to distinguish between ‘theory’ and ‘facts’, with the latter imagined to be unmediated by any theory or biases. This view betrays a belief in the existence of something like ‘true’ History (or, as the 19th century German historian Leopold von Ranke would write, History ‘as it actually happened’): the assumption that historical facts can be re-constructed by rigorous, objective, scientific analysis. At the same time, such deference to historical objectivity is believed to reflect the political neutrality of the historian and academic.

Alongside a distrust for theory, this belief in the possibility of reconstructing ‘real facts’ with a politically neutral stance brings about an illusory myth that consciously or not sweeps under the carpet a number of patent difficulties. It fails to give due credit to the deep complexity of ‘scientific objectivity’ and ignores the fact that any retelling of history (whether ancient or modern) is after all a story-telling, a discourse, which necessitates interpretative choices on behalf of the historian. It also disregards, or openly distrusts, the concept that human knowledge is ‘situated’ – namely, that it reflects the particular conditions in which it is produced, as well as the social identities of its producers.

Since these objections to the idea that there is anything close to an ‘unmediated’ view of the ancient world are famous, one would think that Classicists would know better. Yet, this blind belief in objective history and political neutrality is not uncommon in Classics academia. It has recently surfaced in an op-ed against the decolonisation of Classics curricula in the form of the tenet that students and scholars must remain distinct from their objects of academic enquiry.

But are we ever fully distinct from our objects of enquiry? Is it possible to obtain complete detachment from the historical and social constraints that continuously shape our intellects? Or is this idea of objective and scientific detachment, as Dan-el Padilla Peralta puts it, no more than ‘a privileged fantasy’?

As argued by Patrice Rankine in the aftermath of the 2019 SCS meeting, the supposed objectivity and ‘scientific’ rigour of classical philology and the myth of academic meritocracy have long gone hand in hand, and the interests they have served have been far from politically neutral. Both a devotion to historical objectivity and the appeal that Classics scholars and teachers should steer clear of the political are supported by practitioners whose (nonetheless political) agendas promote the preservation of a status quo, one that continues to benefit those who already hold the privilege of, among other things, not having to think about race.

This is a rare and precious privilege to have, and, as recently shown by the #blackintheivory Twitter hashtag, it shields white academics from huge amounts of distressing interactions, micro- and macro-aggressions, harassment, discrimination, isolation, emotional labour. Yes, even in – or especially in – Classics.

So it is not too much to ask white Classicists to reflect more thoroughly upon our propensity to avoid talking about race in the ancient world. May this have anything to do with those blind-spots brought about by our own white privilege, and the liberal colourblind ideologies that have long nurtured and nourished us?

***

So what happens if we give Race Theory and Critical Race Theory a try and see how they change our picture of the ancient world?

It is true that antiquity predates both the advent of scientific or biological racism in the 17th-18th century and the first emergence of racial concepts in late medieval Europe. But this does not mean that concepts of race and race formation borrowed from Race Theory cannot be productively applied to the ancient Mediterranean.

From a pedagogical perspective, thinking about race in the ancient world is particularly valuable: it allows students to delve deep into the ancient material while acquiring conceptual and analytical skills that also equip them for interpreting and understanding the contemporary world.

Race is far from a straightforward concept, and what we should do first of all is to ask students what they think it means. The same goes for Racism. Hopefully, a tension between ‘biological determinism’ (race as biologically determined, innate and unchangeable) and ‘sociological constructivism’ (race as determined by sociological and historical factors, changeable and contingent) will come out already from the students’ answers. Some may already know that race does not have a biological foundation (with the relationship between phenotypes and genes being too complex to be of any significance) and that the positions of ‘racial naturalism’ and ‘essentialism’, namely that races bear heritable biological properties which explain behavioural predispositions, have long been rejected both by scientists and sociologists.

This leaves us with the position of having to define race as a social and historical process based on perceived human variation (‘Racial Formation Theory’). Some believe that we should retain the concept of race as something that, however illusory, describes very real social, historical and cultural phenomena (‘racial constructivists’), while others would prefer to get rid of a concept that does not refer to anything real in the world (‘racial skeptics’). Regardless of whether we keep the concept, we’d better speak of race as a process: of ‘to race’ as a verb (equal to ‘racialize’); of ‘racialized groups’ rather than ‘races’.

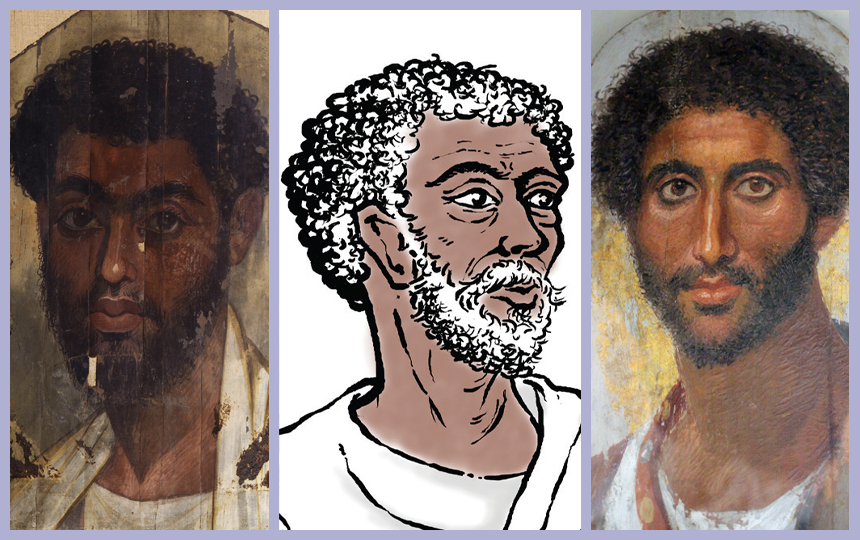

As thoroughly investigated by Frank Snowden Jr., the Greeks and Romans did not seem to distinguish on the basis of skin colour. While this colourblind view of antiquity can and has been put under scrutiny, it does not mean in any case that the ancients were incapable of ‘racializing’. Indeed, both Benjamin Isaac and Denise McCoskey accept the existence of a kind of proto-racism in antiquity. There are of course important differences with later conceptualizations of race: for instance, racial differentiation in antiquity seems to have been based more on location and climate rather than appearance, as exemplified by the Hippocratic treatise ‘On Airs, Waters, Places’. But there are also telling similarities between proto- and later racisms, as is the case of the collapsing of human variation into a single Greek vs. barbarian opposition following the Persian Wars, which is to McCoskey ‘the closest parallel in antiquity to the modern racial binary of “black” and “white”’.

***

So we may easily apply Race Theory to the study of the ancient world. But what about Critical Race Theory? It is important to differentiate between the two, since only the latter (recently attacked by Donald Trump in his ban of antiracist training) is openly antiracist, and explicitly pedagogical. In its main tenets, included in a brief introduction to CRT in UK education, CRT attempts to expose the reality and ordinary nature of structural racism and white privilege, while placing special importance on the voices and experiences of people of colour in order to understand the everyday reality of racism.

While it is true that CRT, which is used to analyse societies that postdate the invention of biological racism, cannot be applied to the ancient world, the same does not follow for the discipline of Classics and the scholarship on which we continue to base our knowledge of the Classics. As Shelley Haley puts it, ‘the interpreters of these ancient societies were or are intellectuals of the nineteenth through twentieth-first centuries, and so have internalized (consciously or not), the values, structures, and behaviors that foster the need for critical race theory’.

While I believe that we are soon going to see more specific applications of CRT to Greek and Roman texts, I follow an important talk by Margo Hendricks, recently highlighted and discussed by the society Eos Africana, in noting from now that there are aspects of CRT that we can all start to apply easily to our study of the ancient past. First, as Ancient Race Studies become more and more common practice among white scholars and teachers, we must be careful to acknowledge the genealogy and ancestry of ideas, reminding ourselves to foreground the black and brown voices that made certain conceptualisations possible. But we also should not forget that the value of CRT lies in the fact that it forces us to apply a ‘bidirectional gaze… one that looks inward even as it looks outward’.

This may perhaps lead us closer to the myth of historical accuracy and objectivity than any prescription to detach ourselves from our objects of study will ever do. And it may make us better teachers, as well as better, perhaps even more honest, intellectuals.

Previous: Centring Africa in Greek and Roman Literature, while Decolonising the Classics Classroom.

Alla - Din / shutterstock.com