What is a sensitivity reading, and how is it done? In this post, Pria Jackson reflects on her EDI work for the new edition of the Cambridge Latin Course, and on what the process can bring to our classrooms and our representations of the ancient world.

Submitted by Anonymous on Thu, 03/08/2023 - 13:12

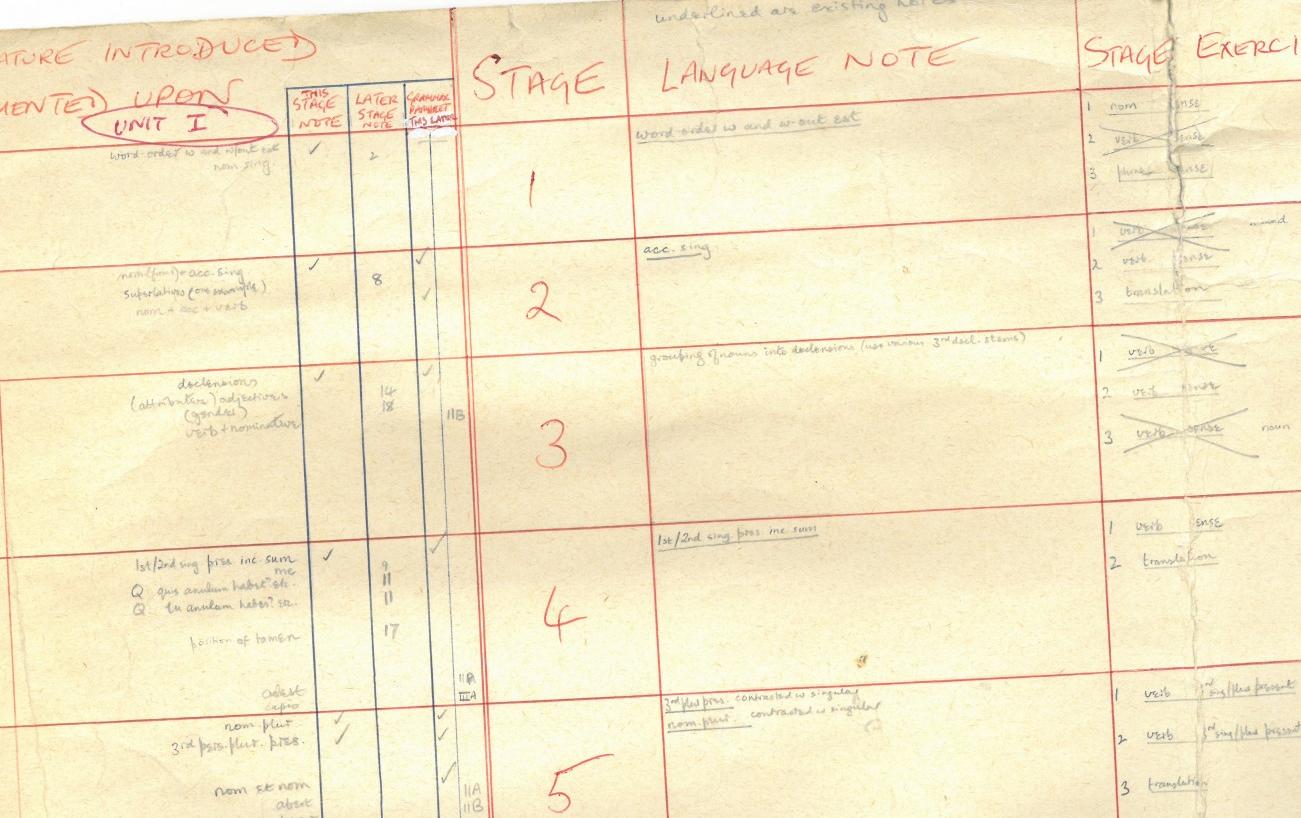

Introducing Queen Catia, who has not only a name but a stronger presence in the UK 5th edition of the Cambridge Latin Course.

When I was first asked to read the latest edition of the Cambridge Latin Course for “matters of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion” I was wary. I had never heard of a textbook using dedicated EDI readers before. My mind wandered back to my own nostalgia-tinged memories of using the CLC as a student and I was unsure of how bringing on an EDI reader could be of value. Not to say the Romans were perfectly equitable in any sense of the word but Caecilius & co. were supposed to be far removed from the burdens of modern politics. In fact, for me at least, that has always been part of the appeal of ancient studies. As a black person, so much of my life is defined by how race gets constructed around me that, when I first started studying the ancient world, it was a spectacular relief to consider a world removed from all that, a world where race didn’t exist. It was as cathartic a mental exercise in the reality of the past as the Black Panther movie was an exercise in the possibility of the future. What then, I wondered, could an EDI reading offer to a story centered on the life and times of people in Roman Pompeii, Alexandria, Britain, and beyond?

It wasn’t until I saw the first draft of the manuscript that I realized that having an EDI reader would be a great boon to the process indeed and, in fact, it reflected a considerable amount of foresight on the part of the editors in hiring one for this project, a thing few other textbooks take the initiative to do.

The truth of the matter was that the new CLC was not going to be as I remembered it, but in all the best ways!

In a sense this was always bound to be the case – our memories are fallible after all. It is much easier to keep the good and glowing in mind instead of dwelling on the rougher, more discomforting patches like Melissa’s not-so-subtly implied role as a sexually available object for Caecilius’ entire household. In other ways though, it became very quickly clear that the designers of this latest version were not trying to edit the past but rather, they were taking a stand on how issues of EDI come into play when one is considering how the ancient world is talked about and taught in the modern classroom.

The ancient world is lost to us. We will never be one of the ancients and we will never return to any “glorious past” that is often overly idealized anyway. We can try to understand how ancient peoples thought by analyzing the remnants they left behind but in the end we are not them. We are us. We are products of our age and our society and as such our own modern social filters are fated to constantly distort our understanding of the past in unavoidable ways. And that is where the intervention of an EDI reader becomes necessary because it is that distortion that is being accounted for.

So, what is an EDI reading?

EDI reading (also called sensitivity reading) is simple. It is the process of reading a text before its publication with an eye towards the impact the text will have on its intended audience. It is noted how the text handles challenging or charged topics of conversation and, if this is handled poorly or is likely to have an overwhelmingly negative impact on the intended audience, changes are suggested and made.

This is hardly a new or revolutionary idea – considering what sort of impact a text would have on its readership has always been a tacit part of the role of the editors and has been happening for new editions of texts since well before Shakespeare. In my opinion, Doris Bass said it best in 1973 when asked about revising new editions of Roald Dahl’s children’s books.

To be sensitive and responsive to the changes in consciousness over the past decade isn’t liberal or reactionary (terms which have primarily political connotations) nor is it censorship. It’s just trying to be ‘good people’ as one’s own awareness of other people’s needs and feelings [are] expanded.

What is new is the recent push to have this task of the editor be set aside, explicitly highlighted, and, in some cases, outsourced as the Cambridge School Classics Project chose to do here. By separating out this task from the already full plate of the editor, the task can be given full consideration.

How is it done?

Like most good things, a proper EDI reading starts with a cup of tea. To read a text not for content but for the impact that content may have requires you to read quite slowly and carefully. This ensures that each section is given thorough consideration but does take a considerable amount of time (hence the tea).

I prefer to read each manuscript at least 3 times; the first reading is done without taking notation. This way I can get a sense of the whole story as a student might encounter it. The second read is done side by side with the old edition. By doing this, I can see more clearly what was changed by the writers and why. This also allows a chance to see the “invisible changes” that are easy to miss – the changing of a name, the omission of a story, etc. Before my last reading I like to take at least a day’s break. This allows me time to clear my head and consider the thoughts I’ve had in full. This is also when I like to do a bit of research if something has raised an EDI flag that is outside of my direct experience. I am hardly the world authority on every lived experience after all. Finally, after all this, when I return for the third reading, I can proceed with adding my review in a clear manner, noting down what changes make sense, which are confusing, and which can be considered highly risky.

In process, truly, an EDI reading is just the same as any other editorial work.

Why use EDI readers for the CLC at all?

The Cambridge Latin Course, in all its iterations, has had a profound impact on its audience. Each printing since 1977 has endeared itself to the hearts of students and teachers who have used it to access Latin. The CLC explicitly uses this to bolster language retention; it is through our students’ connection with the characters and investment in their lives that memorable, deep learning takes place. To this day, I still vividly recall the final heartrending words Metella spoke to her dying daughter in the North American 5th edition whenever I go to ponder the full force of the difference between the present and perfect tense!

The connection students are expected to forge with these characters can be undermined, though, if they themselves have been left out of the imagined intended audience. By using dedicated EDI readers the chances are ever higher that students of diverse backgrounds aren’t overlooked, allowing them the chance to have the same fun and impactful journey through the Latin language as everyone else.

Cambridge School Classics Project